Caste and Catholic Christianity in Colonial and Postcolonial Punjab

This project focuses on the construction of social and religious boundaries among Christians in colonial and postcolonial Punjab, and especially the ways in which caste and untouchability were reinterpreted and renegotiated as part of interactions between European Catholic missionaries and local Christians. I am particularly interested in the figure of the babu, or “native catechist”, and how such local “Bible teachers” acted as mediators between untouchable and low-caste Christian communities on the one hand, and the European-dominated church hierarchy on the other.

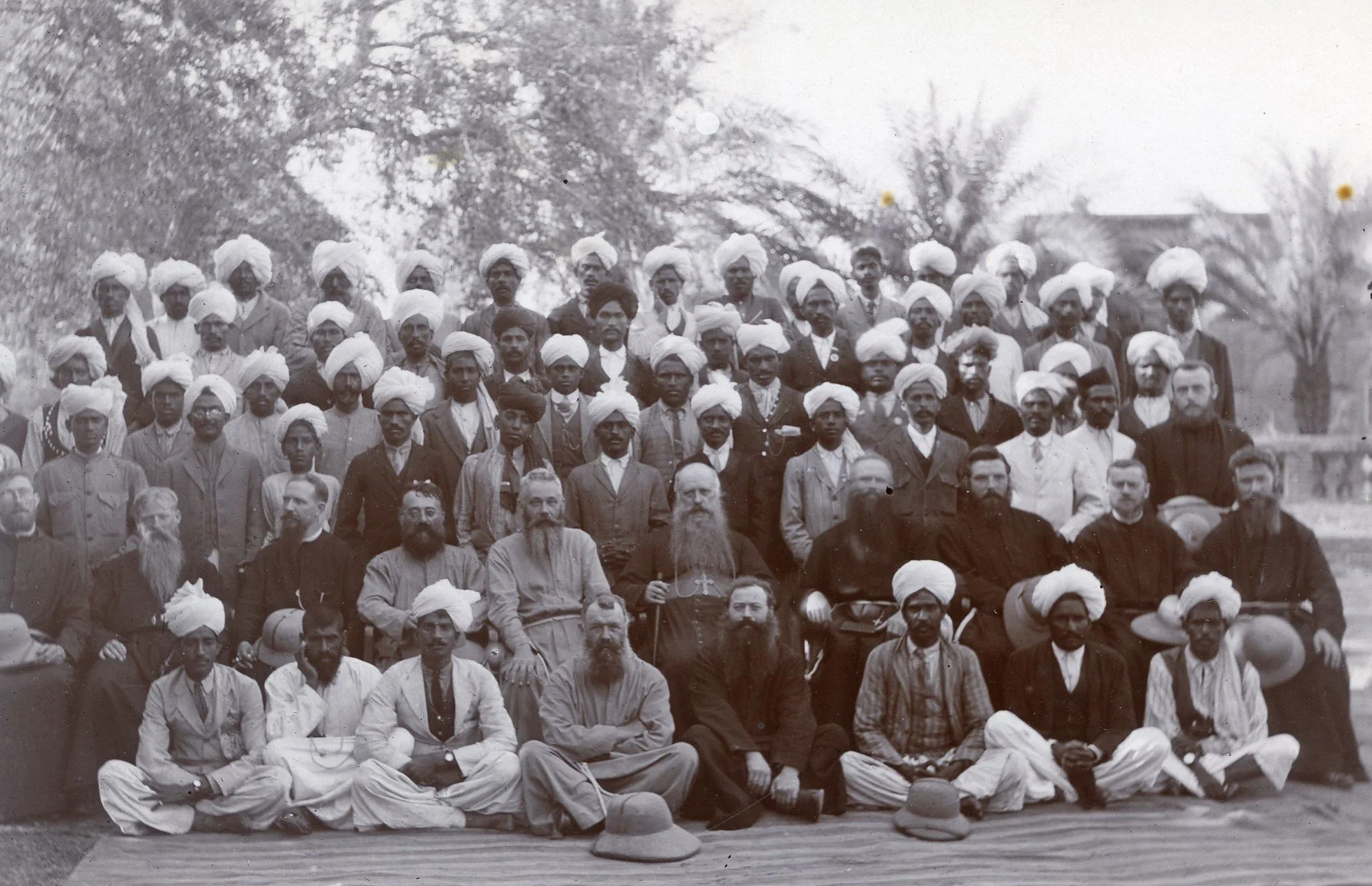

A group of catechists with Flamish Capuchins, c. early 20th cent (Credits: KADOC Leuven, Belgium)

While European missionaries controlled access to resources and crucial channels of communication with foreign donors throughout the colonial period, their actual presence was thin on the ground due to perpetual staff shortages. As a result, native catechists and other local assistants to the clergy often filled the vacuum left by itinerant priests who visited their widely scattered congregations only infrequently. This was particularly true with regard to rural Christian communities, whose numbers, as a result of group conversions from the turn of the century onwards, came to exceed those of urban Christians. By effectively replacing the priest in their day-to-day ministries, native catechists assumed a key role in interpreting scriptures and adapting religious ideas and beliefs to social realities and concepts on the ground, including those related to caste and untouchability. Despite their central role, though, the contribution of native catechists to the reshaping of socio-religious boundaries in Punjabi Christianity has been largely obscured in the historiography, in which the figure of the missionary “pioneer” still looms large.

“The Catholic colonies that emerged during this time period, many of them founded by people from untouchable backgrounds, still form the backbone of Pakistan’s Catholic community.”

For this project, I analyze correspondence, reports, statistics, photographs, and other archival material related to the Flamish Capuchin mission to the Punjab which are being held at the Documentation and Research Centre on Religion, Culture and Society (KADOC) of the Catholic University Leuven, Belgium. Flamish Capuchin missionaries not only erected the Catholic diocese of Lahore in the late nineteenth century, but were also instrumental in founding a number of Christian settlements in the Punjab’s “canal colonies”, newly-irrigated tracts of land that were distributed by the colonial government to various groups of settlers, mostly dominant landholding castes, but also Protestant and Catholic missions. The Catholic colonies that emerged during this time period, many of them founded by people from untouchable backgrounds, not only survive until today, but still form the backbone of Pakistan’s Catholic community, which, apart from a small Goanese minority in Karachi, is dominated by ethnic Punjabis. By reading materials from this mission archive against the grain, my project makes visible and audible the voices and histories of people hitherto obscured in the historiography of South Asian Christianity, and foregrounds their agency in utilizing mission institutions and structures for a radical reinvention of narratives of social belonging.

I supplement the materials from this rich and hitherto untapped archive with vernacular writings by native catechists published in Christian periodicals or in the form of pamphlets and books. I argue that by discussing caste and untouchability in their writings, and by performing a specific understanding of these categories as part of their everyday ministry to local Christians, native catechists were crucial for reshaping perceptions of religious and social belonging on the ground. By foregrounding the voice of local Bible teachers, which is both subtly present in mission sources and expressed directly in their own writings, and by relating their perspectives to larger discussions about religion, caste identity, and social belonging in the context of South Asia, my project contributes to a decolonization of the history of Christianity in the Indian subcontinent as well as to larger debates about caste and religious identity in nineteenth- and twentieth century South Asia.